Legalization of “chocolate cars” brings in 7.302 billion pesos; in 2026, imports tighten and environmental rules carry more weight

The legalization of used vehicles of foreign origin—popularly known as “chocolate cars”—brought in 7.302 billion pesos for public finances between 2022 and 2025, according to Mexico’s Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP). The funds, the agency said, were directed to repaving projects in different states, under a program that had a particularly strong impact in northern border states, where these vehicles tend to be concentrated.

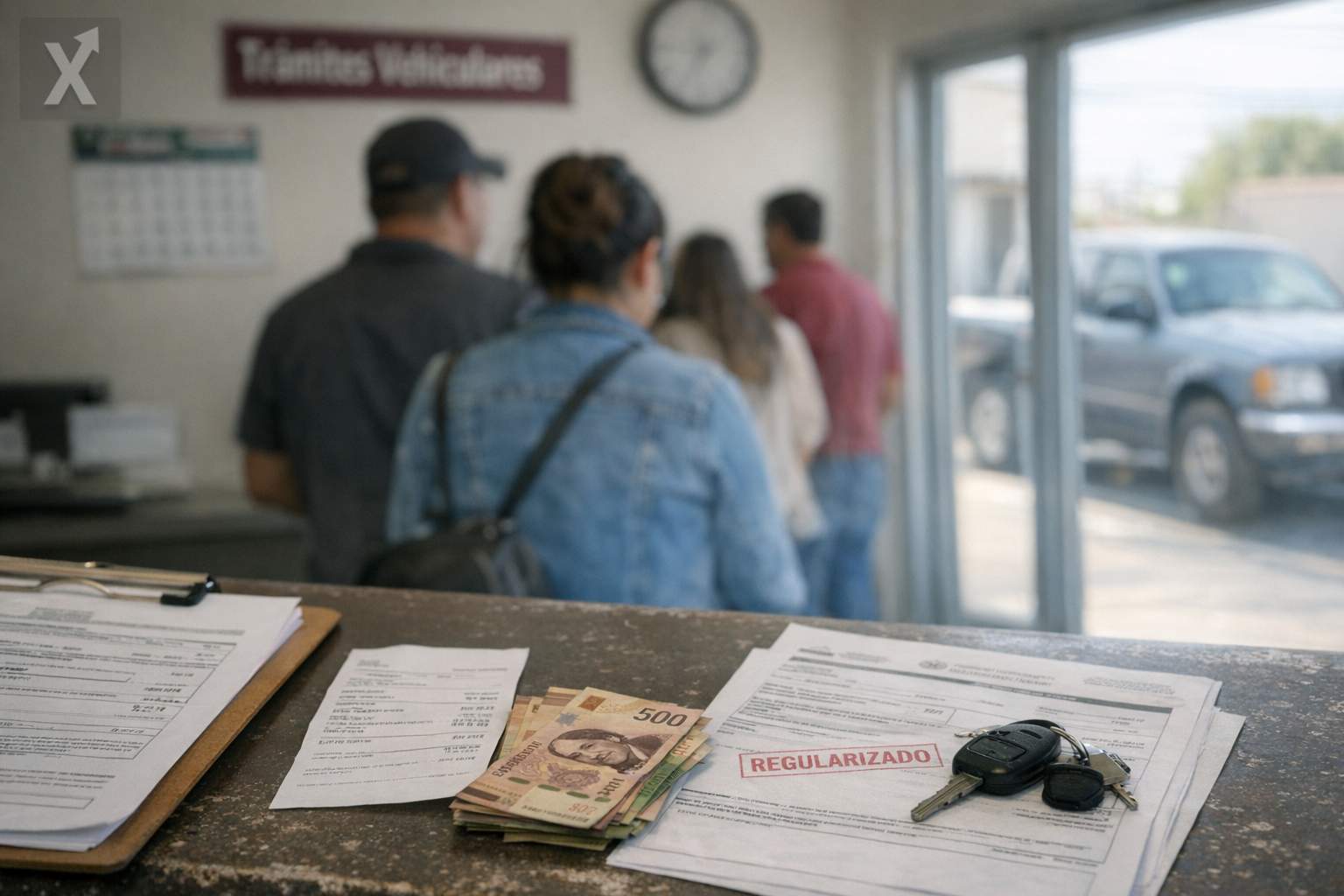

Finance reported that the revenue came from the legalization of 2.98 million vehicles, based on records from the Public Vehicle Registry (Repuve), under the decree issued on December 29, 2022. The scheme aimed to provide a legal pathway for vehicles that had entered the country before October 19, 2021, through a flat payment of 2,500 pesos per car, plus the corresponding registration.

From a fiscal standpoint, the amount collected amounts to an extraordinary, limited source of revenue: 7.302 billion pesos is meaningful for local projects, but small compared with the size of the federal budget. For context, Mexico’s total public spending is measured in the trillions of pesos, while tax revenue depends mainly on the VAT (IVA), income tax (ISR), and oil-related revenue. Even so, because the funds were earmarked for road infrastructure, they tend to have a visible and politically sensitive effect: improvements in paving and urban mobility in municipalities with heavy use of imported secondhand vehicles.

The SHCP argued that the program’s social objective—helping people who were already using these vehicles without legal certainty—“was successfully met.” Still, the issue has been controversial due to its side effects: pressures on the formal auto industry and dealers, as well as public-safety challenges (full vehicle identification), local revenue collection (vehicle ownership taxes or annual registration renewals), and the environmental impact of bringing in and circulating older vehicles, generally with less efficient technology and higher emissions.

With the special scheme concluded, Finance clarified that starting in 2026, anyone seeking to permanently import a used car will have to comply with the existing fiscal, customs, and environmental mechanisms, in line with the decree published on November 4, 2024 by the Ministry of Economy and later renewed. The change marks a shift from mass legalization with a uniform fee to an import framework with more detailed technical requirements and differentiated tariffs.

According to the authority, legal importation remains open, but under conditions: vehicles must meet physical, mechanical, and environmental protection criteria, and the additional requirement of a certificate of origin is eliminated; instead, the importer must pay the established tariffs. For the border region, a 1% tariff is contemplated for vehicles five to nine years old and 10% for vehicles more than 10 years old. For the rest of the country, a 10% tariff would apply to vehicles more than eight years old.

This adjustment comes at a time when Mexico’s economy is sending mixed signals: on one hand, supply-chain relocation (“nearshoring”) and integration with the United States continue to support manufactured exports and investment flows in certain industrial corridors; on the other, consumption is moderating as financial conditions normalize, and the cost of credit still reflects historically high interest rates. In that context, demand for imported used cars tends to rise when new-vehicle prices stay high and financing becomes more expensive, making the “formal” import route and its associated costs more relevant.

On the urban and infrastructure front, channeling resources to repaving addresses a recurring problem in border municipalities and mid-sized cities, where the vehicle fleet—often older—puts pressure on streets and roadways. However, going forward, public debate will likely focus on how to balance three objectives: affordability (lower-cost vehicles for households), safety and legal certainty (registration, traceability, anti-theft efforts), and sustainability (emissions standards and mechanical condition). The move toward stricter rules suggests the environmental component will carry greater weight in public policy related to used-car imports.

Final note: the mass legalization effort ended with meaningful revenue for road projects and nearly three million units added to the formal registry, but the rule change for 2026 points to a more regulatory and selective approach. The challenge will be to maintain a legal and transparent import pathway without encouraging informality, while raising mechanical and environmental standards in a market where the price of a car remains a decisive factor for households.